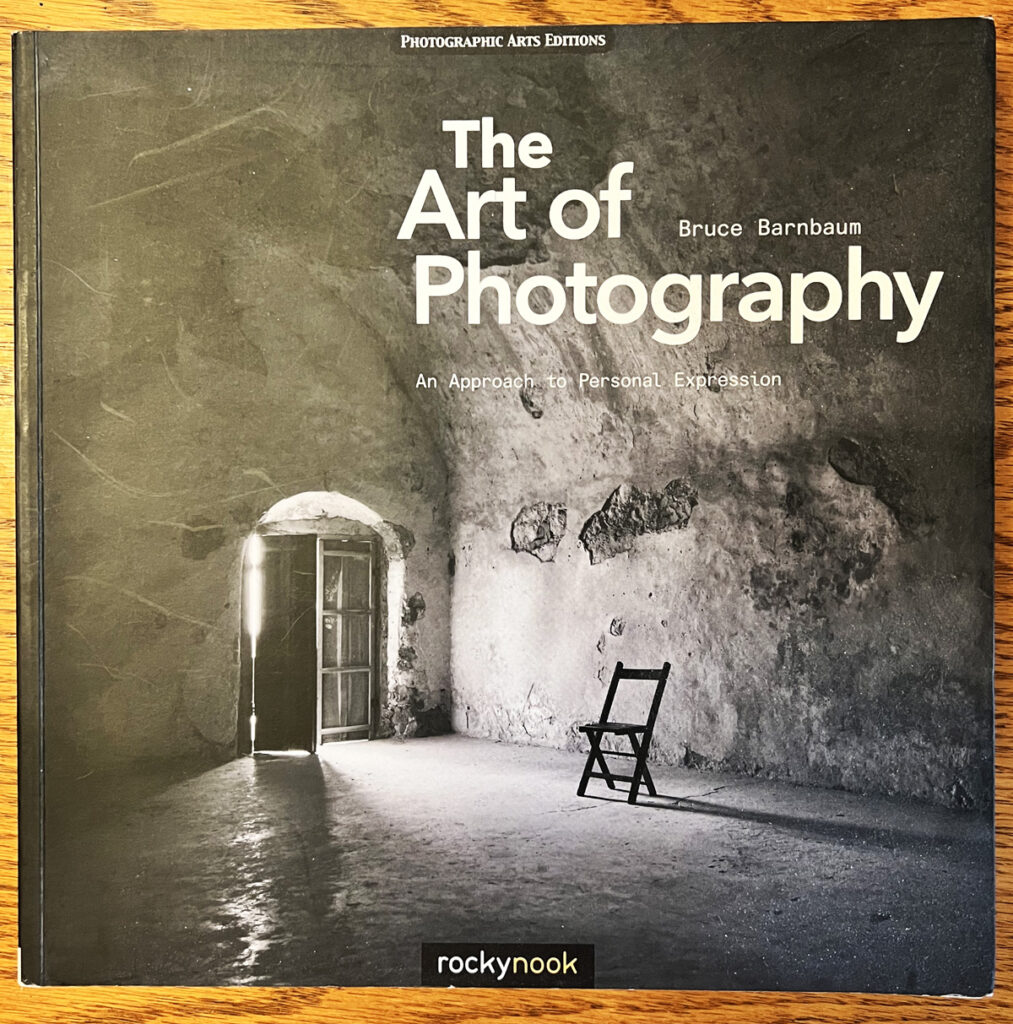

On a recommendation from Jim Blomfield I recently purchased a copy of Bruce Barnbaum‘s book, The Art of Photography, first published in 2010 and now – already – in its fourth printing.

Jim was right; this is a great book, certainly ranking in the top five in my library. I purchased the book mostly because I have been a fan of Barnbaum’s black-and-white images for several years, and I wanted the book as a resource for helping me produce the finest gelatin silver black-and-white prints I possibly can. That detail – on characteristic curves, dodging and burning, paper flashing, etc. – is in the later chapters and provides some superb background for image-taking and darkroom technique, to complement my other excellent volumes on darkroom technique by Ansel Adams, John P. Schaefer, Henry Horenstein, and others.

But what makes Barnbaum’s latest work important for every photographer, colour or black-and-white, film or digital, are the introductory chapters on composition, light, simplicity vs. complexity, line and form. These chapters make excellent reading, and provide the most lucid description I have yet read on what characteristics make a good photograph. Here is a brief excerpt from page 50:

Of course, in well-crafted photographs these elements (lines, forms, etc.) are not abstract things but real things (tree trunks, faces, clouds, buildings, shadows, etc,). A good artist relates real things to one another as abstract elements to see if they work together successfully , or if they fail.

[…..]

All too often a photograph fails because it is strictly an “object” photograph: an isolated object of visual interest. The object exhibits no interesting relationship to anything else in the photograph, and the remainder of the image is strictly background. With rare exceptions, such photographs are mere documentation of objects; lacking internal relationships, they fail artistically.

Even if there is a central object of overwhelming importance, a photograph of it is usually enhanced when it can be related, however subtly, to other elements in the image space. Visual relationships spawn visual harmonies and impart heightened interest. Most photographers start out with an overriding concern with subject matter. As time goes on and they become more sophisticated, their emphasis turns more toward studies of light and form and the wonderful relationships that exist among the elements of the scene-even in the context of a particular type of subject matter that intrigues them.

It is this material on composition – similar in depth, perhaps, to Freeman Patterson’s Photography and the Art of Seeing – that makes this book so worthwhile.

Highly recommended.